Larissa Sansour, A Space Exodus. Video (5` 29"). 2009.

“Jerusalem, we have problem,” a woman’s voice says, as female fingers run over the controls of a space ship. “No . . . We are back on track,” she then mutters, breathing heavily; the only response from Jerusalem is a deafening silence. In a white spacesuit bearing her name, a Palestinian flag, and embroidery that looks like traditional tatrizz, the woman lands on the moon and plants a Palestinian flag. “A small step for a Palestinian, a giant leap for mankind,” her voice echoes through her space helmet. She waves to planet Earth; the camera pans down to her boots bouncing on the surface of the moon, and eventually pans out as she leaps, floats, and fades away into outer space.

Clip from A Space Exodus by Larissa Sansour on Vimeo.

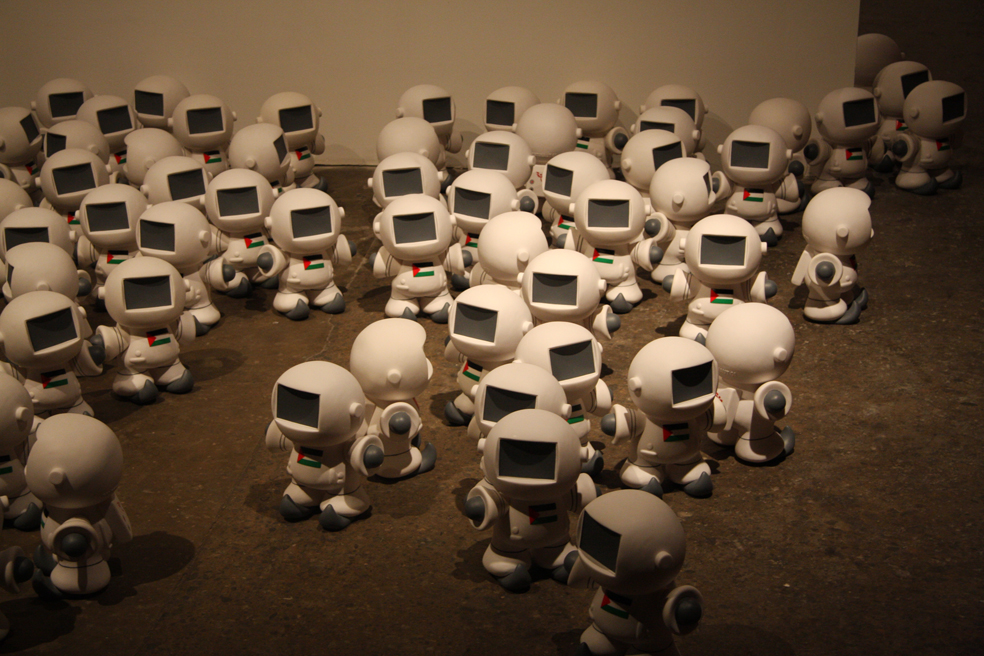

Somewhere between an autobiography and a political commentary, Larissa Sansour’s 2009 A Space Exodus leaves us grasping for meaning. A Space Exodus has been screened at film festivals as a stand-alone film and as part of an artistic exhibit in museums and galleries – the exhibit combines the video-clip, still photographs from the video, and an installation of multiple vinyl sculptures of little Palestinian astronauts (known as Palestinauts) taking over the installation’s floor.

Although carefully choreographed, short, and seemingly simple, A Space Exodus is a difficult film to describe, let alone interpret. Within a five and a half minute stretch of time that is infinite and placeless, between the loaded title (the significance of a “space exodus” so wrought for Palestinians) and the credits, we encounter everything that Palestine and Palestinianness could possibly signify: a palimpsest of meanings.

Is this a fantasy? A dream? A nightmare? The open-endedness of interpretations is what makes this film truly Palestinian.

Is the landing of a Palestinian on the moon a promise of a better future? It can be. The film can certainly be seen as a pastiche of A Space Odyssey: 2001, a homage to Stanley Kubrick and Arthur C. Clarke’s scientific realism and ambiguous imagery. In reformulating the famous words of Neil Armstrong, against what sounds like an ‘Arabized’ version of The Blue Danube (part of the original soundtrack in A Space Odyssey), Palestinians have embraced the promises of progress and technology, and co-opted one of (wo)mankind’s finest moments. The “exodus” is a new beginning, one pregnant with the liberation that can accompany exile.

Alternatively, the planting of the Palestinian flag also suggests that the farther we go from our homeland, the farther we are from Jerusalem, we still manage to establish our presence. Perhaps the film suggests Palestinians’ departure towards a promised land, still forty years away, as they wander not in a desert but in outer space, where they will be granted their own laws in return for their faithfulness by a secular entity. Maybe it is not Jerusalem and planet Earth that fade away, but Palestinians’ continuous limbo that does. The film could equally be about a new time-place possibility of a magical Palestinian displacement, far away from daily difficulties. The moon, a new Palestine: a land without a people for a people increasingly without land.

Or does the film communicate a kind of anxiety – specifically Palestinian, traumatically exilic, yet universal when it comes to “technological advancement” – that should we leave planet earth, we risk never being able to return? That too. As such, the film is equally a warning against adopting Western measures of success, suggesting that if we dream according to the West’s gauges of progress we might end up getting lost. It thus also serves as a metaphor for the “roadmap” (the West’s idea of a “peace process”) on which we’re still not sure whether “we are back on track” or not, or if we even want to be.

Or is it about our ongoing exile from the world, one from which we still have to garner a response and support? Reminding us of our global predicament: thrown out, not into the sea or the desert, but into outer space. The film then is also a vision of our nightmare: unheard and faded into nothingness.

Or perhaps it suggests that our forced exodus is doomed to remain private – nobody hears her, nobody responds, she’s all alone in outer space, her voice remains trapped in her helmet, her body free-falling, fading into black. Nobody cares. In a twist on another famous Palestinian icon, Handhala, it is the audience that is rendered the helpless, mute witness. The film could then also be a message about the hollowness of our de-territorialization and the loss of our continuous temporality: even if we follow our dreams to the edge of the universe, even if we plant our flag on new territory, we will still feel defeated, we will still be lost, if there is no communication, no response, no connection to Jerusalem.

Who, what, where, is Palestine? The woman. The radio silence. The spaceship. The moon. The lone flag. Planet Earth shrinking against the star-studded black sky . . . All of them. A Space Exodus communicates the acutely solitary experience of Palestinian exile, the refractions and discontinuities of our loss of time and space. But it also allows us the dream of a return to an organic and binding connection. It is both a quest and a eulogy for the wholeness of self and of nation, both a preoccupation and celebration of deterritorialization, displacement, un-belonging, forgotten-ness. In other words, the film does three contradictory things at once: it denies us a return, it takes us home, it keeps us wandering and homeless.

A Space Exodus breaks away from a unified Palestinian narrative and puts everything into question. And that is what makes it truly Palestinian. To discuss Palestine, Palestinianness, or Palestinian cinema puts us in the quandary of dealing with the notion of the “national,” to assume some central overarching story, some shared meta-narrative. But that is neither true of Palestine, and certainly not of Palestinianness, anymore, and perhaps never was. Ten million of us are defined well outside the comfort of a political solution to our “problem” (not “our” problem to begin with, but that’s another matter). We are, individually and collectively, a fragmented paradox. We should then expect a truly Palestinian film (however we agree to define such a label: made in Palestine, made by a Palestinian, about Palestine/Palestinians, etc., whatever any of those might mean) to reflect the contradictions, the hybridity, the de-centerdness, and the absurdities of what constitutes Palestinianness.

Palestinian cultural production broadly, and cinema specifically, has been enveloped by incessant intrusions of politics into its agenda and into its motifs. This is no different in A Space Exodus in accentuating nationalistic icons: the flag, tatrizz, the centrality of an unseen and unheard Jerusalem, and, in twisting the (other) famous words of Neil Armstrong that the Eagle has landed, the statement that “the sunbird has landed” – a reference to the national bird of Palestine, should a nation-state ever be established. But it is not these symbols that mark the film as Palestinian; it is a different politics, by which I mean a recognition that film (and culture more generally) does not take place outside the historical, political, geographical, and socio-economic contexts that shape it. Various forms of repression impinge upon Palestinian cinematic production: the Israeli state, Arab “host” governments such as Lebanon and Syria, an Orientalist and Islamophobic environment in the diaspora, corruption and nepotism within the Palestinian Authority, the general difficulty of raising funds for film-making and film-distribution, and most of all, the continued strength and intensity of Zionist narratives.

Palestinians may be past the stage of proving their existence against Golda Meir’s fiat that “there is no such thing as a Palestinian people.” Certainly, A Space Exodus can be understood as negating the subjugation and silencing of such Zionist narratives. The film does more, however, in communicating the de-centered, hybrid, and contradictory existence of Palestinians.

Without a single image of an Israeli soldier, without a single line uttered by an older refugee lamenting lost olive and orange groves, without a single depiction of a checkpoint or a wall, without a single shot of refugee camp or an eradicated village, A Space Exodus portrays the continuity of Palestinian pain, trauma, struggle, survival, and hopefulness. Sansour unchains us from the confining jingoism and usual narratives and imageries in most of Palestinian films, whether documentary or feature. In telling the story of Palestine and Palestinianness without explicitly doing so – leaving open what these represent, in all of their contradictions, dynamism, ironies, absurdities, sadness, or humor (the woman, the flag, the moon, all of them) – the film communicates both hope and loss, openness and displacement, a banishment and a new beginning, un-belonging and sumud. Thus the film expresses both the nation and its self-realization, but at the same time offers a critique of these by framing Palestinianness beyond the boundaries of a nation-state, or indeed beyond the borders of identity.

In the ever-lasting effect of its ambiguity, Sansour’s film is both an act of resistance and a weapon of culture. Like Palestine, like Palestinianness, A Space Exodus leaves us with that sense that it may not matter how we interpret the film’s meaning: We, Palestinians, are still here. Wherever and whenever here is.